Photo Credit: Malcolm Lightbody on Unsplash

It is tempting to think that we form our beliefs by a conscious, deliberate process of choosing between alternative theories. That beliefs can be readily updated when they don’t match what we observe, and even discarded when they are no longer useful for explaining facts and predicting outcomes. All these are of course, themselves statements of belief. But how true are they?

Beliefs as soldiers

People instinctively defend their core beliefs against contradictory statements and facts. Core beliefs are beliefs on which one’s group identities (family, community, nation…) are anchored. Religious and political beliefs are typically characterized as core beliefs.

Science may proceed by trying to falsify rather than trying to confirm theories, but we don’t run our lives according to the scientific method. For anyone who is keen to defend their beliefs at any cost there are several easy, catch-all arguments available, some of which we shall look at next.

Context-free Arguments

Let’s say I make the assertion that “astrology does not work”. You could try and counter with one or more of the following —

- Ad-hominem Attack: You are a scientist that’s why you don’t have any respect for traditional knowledge-systems

- Anecdotal Evidence: My horoscope said I would meet an “interesting new person” this week and I did!

- Argument from Authority/Antiquity: Astrology is found in the divine scriptures which have survived for thousands of years

- Appeal to Faith: It doesn’t work for you because you don’t have faith

- Appeal to Popularity: Millions of people believe in astrology and they can’t all be wrong

- Appeal to Possibility: It may seem unlikely but it could work, who knows?

- Shifting the burden of proof: You can’t prove that it doesn’t work

- Deriving an “is” from an “ought”: It would be so nice if we could see into the future

I’ve occasionally found myself using such lines of reasoning to defend my own beliefs. But what exactly is wrong with them?

Arguments of this kind are commonly termed Logical Fallacies, but I like to call them “context-free arguments” because they can be deployed without any reference to the actual content of the belief being defended. If you are not convinced, just replace the original premise with “homeopathy does not work” and see if the same counter-arguments still seem to work with minor modifications!

The Great Filter

How did you form your earliest beliefs about the world? I would argue that it must have happened by an involuntary, unknowing process. The rules of logic and knowledge of the world would have come later. Do prior beliefs act as a filter for interpreting facts encountered later? If so, where does this line of reasoning lead us?

It implies that if we don’t at some point, adopt a consistent, fact-based method for believing and disbelieving, we will be left with the default process which is this — statements that contradict existing beliefs are automatically rejected while those that agree with them (or are neutral) are taken on board. And this process would apply recursively, with beliefs acting on facts acting on beliefs and so on. Our core beliefs would, in this case, be an accident of our birth.

Why does this happen? According to the latest research in cognitive science, our brains value coherence over accuracy — if a more consistent story can be constructed by selecting some facts and leaving out others, then that is precisely what will be done. This is how our brains minimize cognitive dissonance.

Survival of the fittest ideas

When offered a choice between a bullock cart and a car, anyone who can afford the car is very likely to opt for it. When it comes to technology, it’s easy to see how new technologies work better than older ones and that is all that matters — a utilitarian strategy works best here. But is there any sense in which modern science “works” better than what came before it? How do we decide the fitness of beliefs?

Some beliefs are held simply because they are empirically accurate. If you refuse to believe in gravity, you will very soon be forced to revise your position by a falling rock! So everyone believes in gravity [1].

But in many cases, empirical accuracy does not determine the fitness of a belief because there is no possible empirical test for it. For instance, you could easily convince yourself that there is an afterlife, because no one is ever going to be in a position to confirm or falsify your assumption. Such beliefs may be held because they feel good (who wouldn’t like to go to heaven, right?) or to minimize conflict with other members of the family or community.

Wired This Way

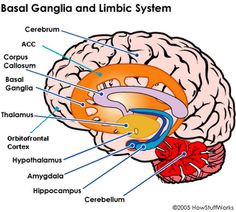

Most people follow not only a religion but also a political ideology based on the family into which they were born. This results not just from environment factors (e.g. childhood indoctrination) but also genetic factors. It turns out that political orientations are correlated with brain structures (which are largely genetically determined), though we should be cautious in interpreting these findings.

Here’s an excerpt from the 2011 study published in Current Biology.

Individuals who call themselves liberal tend to have larger anterior cingulate cortexes, while those who call themselves conservative have larger amygdalas. Based on what is known about the functions of those two brain regions, the structural differences are consistent with reports showing a greater ability of liberals to cope with conflicting information and a greater ability of conservatives to recognize a threat, the researchers say.

Notes

[1] In the folk science sense of the word, people always believed in gravity. Newton’s great insight was to prove that the same force which makes an apple fall to the ground also makes the moon go around the earth.